It's the end of 2011, and I'm posting my 104th book. I didn't quite make it to my goal of 111 in 2011, but it does verify my estimate that I read an average of 2 books a week. Not only that, but I'm pleased that I have managed to complete a blog entry for most of what I've read. Looking back at the year's entries, I see that 11 are unfinished, bearing a promise similar to "Recently finished. Review coming soon!" While I did finish these at some point along the way, I never did make it back to record my thoughts. Maybe I'll go back and add a few lines some time in the future, but more likely I'll simply move forward with the goal of having fewer unfinished entries in 2012. There's resolution #1 for 2012. And, I am challenging myself to read more this year: 112 books in 2012. Perhaps you'll join me?

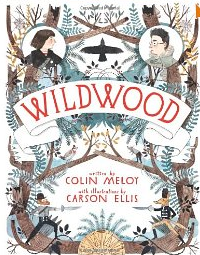

Wildwood is a charming book to end the year with. It's an illustrated novel for ages nine and up, created by a husband (the lead singer of the Decemberists) and wife team in Portland, Oregon. Since all things cool come from Portland these days, it's not surprising that the book is a magical, eco-conscious adventure. The story begins when Prue and her friend Curtis enter the wild area that Portlanders know as the Impassable Wilderness in order to rescue her baby brother. Oddly, but appropriate in Portland, where surfaces are covered with images of birds from the Corvus genus, Prue's brother was stolen by a murder of crows. Immediately upon entering the wilderness to find him, Curtis and Prue are separated and fall in with people from two parts of the hidden world: Prue with a mailman serving the "civilized" North Wood (rural) and South Wood (urban) human and animals and Curtis with a coyote army serving the human Dowager Duchess of the Wildwood. As is usual for books targeting younger readers, animals can talk--and frequently wear clothing. Really, though, it's a wonderful novel for children of all ages who want to exercise their imagination and delve into a world of excitement and hope. I'd highly recommend it as one of your first reads in 2012.

Saturday, December 31, 2011

Thursday, December 29, 2011

103.11: The Lacuna, by Barbara Kingsolver (2009 hardcover)

I have the bad habit of buying the majority of the books I read in hardcover. I could come up with any number of excuses, but it comes down to laziness and impatience: I don't want to wait for the paperback version, and I don't want to take a trip to the library. The worst thing about this habit is that I don't just buy as many books as I can read at a given time. Instead, I simply buy books when I encounter them, and I worry about reading them at a later time. You won't be surprised to hear that this results in a large number (dozens might be a modest figure) of unread books gracing my shelves at any given time.

The reason I'm making this confession is two fold: it is a habit I would like to change, and it sets the premise for this book, which has sat on my shelf for two years since its purchase. When she came by to borrow some reading for the holidays, my friend Diqui saw me reading The Lacuna and exclaimed, "You're just reading that now? I read it over a year ago." The ridiculous thing about this is that Diqui read my copy--borrowed from the very shelves she was perusing. My bad habit is such that this is not an uncommon occurrence, I must confess, and I won't even get into the problem of purchasing duplicate copies of the same book. (My friend Marsha can give you the details there, should you be curious.)

The reason I put off reading The Lacuna is obscure at best. I am, in fact, a big fan of Kingsolver--and of her two most recent novels in particular. I even recall eagerly waiting to get home from the store to read it, and it made it to my bed-side reading stack--a sign of favor in my book hierarchy. However, at some point in time--likely when clearing surfaces for a gathering at our house--the book made its way back to the library shelves and just never reached out to me again. Why I pulled it from the numerous other books awaiting my attention right now is likewise unclear--although partially attributable to me goal of buying fewer books--but I'm glad that it did.

Like The Poisonwood Bible and Prodigal Summer, The Lacuna explores a time and place through the eyes of a primary character: a fictional man interacting with real figures from 1930s-50s Mexico and the US. Harrison Shepherd (who seems so realistic that I had to look him up to make sure he didn't exist), son of an American father and Mexican mother, arrives in Mexico in 1929 with his mother and follows her through a number of living situations--with one two-year stint at a military school back in the States--until he finds himself mixing plaster for Diego Rivera, serving as cook to Rivera and Frida Khalo, and acting as personal assistant to Lev Trotsky. Upon Trotsky's death, Shepherd returns to the U.S. in 1941 and eventually becomes a popular author of novels featuring the Aztec and Maya, at least until the Committee on Un-American Activities catches wind of him. The entire story is told through Shepherd's fictional diaries, fabricated book reviews, and created letters--with 8-10 actual articles and documents mixed between them to add to the realistic tone. It's a riveting read, and it provides one of my favorite ways to learn about history: through the lens of excellent fiction. If you have been thinking about reading this book and somehow, like me, just never got around to it, I'd recommend you do so now.

The reason I'm making this confession is two fold: it is a habit I would like to change, and it sets the premise for this book, which has sat on my shelf for two years since its purchase. When she came by to borrow some reading for the holidays, my friend Diqui saw me reading The Lacuna and exclaimed, "You're just reading that now? I read it over a year ago." The ridiculous thing about this is that Diqui read my copy--borrowed from the very shelves she was perusing. My bad habit is such that this is not an uncommon occurrence, I must confess, and I won't even get into the problem of purchasing duplicate copies of the same book. (My friend Marsha can give you the details there, should you be curious.)

The reason I put off reading The Lacuna is obscure at best. I am, in fact, a big fan of Kingsolver--and of her two most recent novels in particular. I even recall eagerly waiting to get home from the store to read it, and it made it to my bed-side reading stack--a sign of favor in my book hierarchy. However, at some point in time--likely when clearing surfaces for a gathering at our house--the book made its way back to the library shelves and just never reached out to me again. Why I pulled it from the numerous other books awaiting my attention right now is likewise unclear--although partially attributable to me goal of buying fewer books--but I'm glad that it did.

Like The Poisonwood Bible and Prodigal Summer, The Lacuna explores a time and place through the eyes of a primary character: a fictional man interacting with real figures from 1930s-50s Mexico and the US. Harrison Shepherd (who seems so realistic that I had to look him up to make sure he didn't exist), son of an American father and Mexican mother, arrives in Mexico in 1929 with his mother and follows her through a number of living situations--with one two-year stint at a military school back in the States--until he finds himself mixing plaster for Diego Rivera, serving as cook to Rivera and Frida Khalo, and acting as personal assistant to Lev Trotsky. Upon Trotsky's death, Shepherd returns to the U.S. in 1941 and eventually becomes a popular author of novels featuring the Aztec and Maya, at least until the Committee on Un-American Activities catches wind of him. The entire story is told through Shepherd's fictional diaries, fabricated book reviews, and created letters--with 8-10 actual articles and documents mixed between them to add to the realistic tone. It's a riveting read, and it provides one of my favorite ways to learn about history: through the lens of excellent fiction. If you have been thinking about reading this book and somehow, like me, just never got around to it, I'd recommend you do so now.

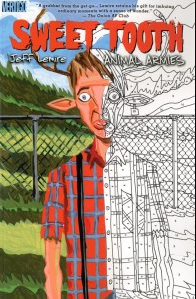

101-2.11: Sweet Tooth, Volume 2 "In Captivity" and Volume 3 "Animal Armies," by Jeff Lemire (trade paperbacks, issues 6-11 and 12-17, 2010/11)

The other day when we were talking about the "value" of different leisure activities--watching TV, reading, playing Xbox, crafts, etc.--my husband Eddie made a disparaging comment about Sweet Tooth. I was a bit offended at first and asked him what he knew about it. He said he had picked up and flipped through one of my trades when it was sitting on the coffee table at my sister's house. It isn't real literature, he suggested, and I suppose he is right to some extent. It's not the type of thing I would likely read in public--unless that public involved a high number of comic readers--so even I must confess to a degree of speculation. The cover pictures themselves likely lead some of you to raise an eyebrow. A boy with antlers? A girl with a pig snout? Yet, here I am writing about the series on my blog, so I'm not THAT embarrassed.

While I wouldn't be willing to take a side defending Sweet Tooth as a great work of literature, it has some significant merits that put it solidly in the literature realm. The plot is interesting and engaging, the characters are complex, and it addresses societal issues in the guise of metaphor. You see, it's not just that these kids have animal features: some folks don't believe they exist; others know and fear them; and still others--the minority--know and love them. It's mainly the parents of the hybrids that fall into the later category, as the women gave birth to these humans with animal characteristics after a plague struck the U.S.--killing the majority of people and sending things into complete disarray in a short period of time. Unfortunately, that same plague usually kills the parents before too long, leaving the kids alone and defenseless against those fighting for survival. From the very start, the antlered Sweet Tooth--so called for his love of candy--is a sympathetic and endearing character; perhaps it's some built-in Bambi reaction, but I want him to make it. It's an up and down struggle, of course, in the world drawn in these books, and I'm sure the battle will continue throughout the series. Along the way, the premise allows for an exploration of bigotry and fear, what it means to be human, and good versus evil (and shades in between). And, Lemire's story and art are both strong enough for me to continue that exploration--despite a shade of embarrassment.

While I wouldn't be willing to take a side defending Sweet Tooth as a great work of literature, it has some significant merits that put it solidly in the literature realm. The plot is interesting and engaging, the characters are complex, and it addresses societal issues in the guise of metaphor. You see, it's not just that these kids have animal features: some folks don't believe they exist; others know and fear them; and still others--the minority--know and love them. It's mainly the parents of the hybrids that fall into the later category, as the women gave birth to these humans with animal characteristics after a plague struck the U.S.--killing the majority of people and sending things into complete disarray in a short period of time. Unfortunately, that same plague usually kills the parents before too long, leaving the kids alone and defenseless against those fighting for survival. From the very start, the antlered Sweet Tooth--so called for his love of candy--is a sympathetic and endearing character; perhaps it's some built-in Bambi reaction, but I want him to make it. It's an up and down struggle, of course, in the world drawn in these books, and I'm sure the battle will continue throughout the series. Along the way, the premise allows for an exploration of bigotry and fear, what it means to be human, and good versus evil (and shades in between). And, Lemire's story and art are both strong enough for me to continue that exploration--despite a shade of embarrassment.

Sunday, December 18, 2011

100.11: Term Limits, Ex Machina Volume 10, by Brian K. Vaughan (writer), Tony Harris (artist), and JD Mettier (colors) (2011 trade paperback, issues 45-50, 2009/10)

Two of my favorite comics are Runaways and Y: The Last Man by Brian Vaughan. Actually, I should say were my favorites, as both series were concluded some time ago. Once in a while another writer/artist combo will pick up the Runaways and complete a new story arc, but they are never as good as Vaughan's originals. So, the best I can do to follow Vaughan's current work is Ex Machina. And that's pretty darn good in itself.

Two of my favorite comics are Runaways and Y: The Last Man by Brian Vaughan. Actually, I should say were my favorites, as both series were concluded some time ago. Once in a while another writer/artist combo will pick up the Runaways and complete a new story arc, but they are never as good as Vaughan's originals. So, the best I can do to follow Vaughan's current work is Ex Machina. And that's pretty darn good in itself. It looks like I haven't reviewed Ex Machina yet on this blog--I'm a bit behind in my comic reading and just catching up--so I'll fill you in on the premise. Mitchell Hundred is an engineer/architect who comes in contact with an otherworldly item in the water, which leaves him with the ability to talk to machines and command them to do his bidding. With the assistance of two friends, he becomes a local NYC hero, rescuing babies and the like. The police consider him a vigilante and try to track him down, but after September 11, 2001, when he uses his abilities to stop the collision and collapse of the second Twin Tower, he becomes a community sensation. Having been raised by an activist mother, he decides to turn his new acclaim to public service and politics, turning celebrity into a position as NYC Mayor. In this position he fights the forces of evil--both political and supernatural--that threaten his people.

In trade 10, NYC Mayor Mitchell Hundred continues to fight the good fight against forces threatening his city--and now the world. In this story arc, a reporter becomes infected with an ability akin to Hundred's, with an evil twist: she can speak to humans and command them to do her bidding. Add the fact that she is acting on behalf of horrible monsters in another dimension who are seeking a gateway to ours, and it's a job for the super mayor. The volume ends with both relief and darkness, and readers are left to consider whether the system is leading Hundred down a path of corruption. And, I suppose it's fitting that Vaughan leaves us there, since issue 50 concludes the series. For first-time readers, that can be a good thing, as you won't have to wait for future issues to come out.

The plot is a bit absurd, but superhero comics require enemies, and they are harder to come by these days. Besides, it's the issues and discussion around the main plot that make this series interesting. Hundred's political rise from nobody to mayor of NYC, and his rumored candidacy for US office, are what make this comic worth reading. Hundred has made his reputation as an Independent, making decisions based on what he sees as best for the people of NYC instead of a specific political agenda. While he backed gay marriage, he rejects the morning-after pill, and he's hard to pin down on most hot-button topics. Additionally, the series is purposely self-conscious, throwing out one-liners about comics all the time. It makes for an interesting blend of politics, current events, and super heroism that's hard to resist.

Saturday, December 17, 2011

99.11: Dead Man's Knock, The Unwritten Volume 3, by Mike Carey & Peter Gross (script, story, art), Ryan Kelly (finishes) (2011 trade paperback, issues 13-18)

This is the first blog entry I'm writing on my iPad, using an app called Blogger+. My new plan is to write and upload text whenever/wherever I finish a book (hotel, bed, a coffee shop) and then add the finishing touches (pictures, links, and proofreading) when I am at a desktop computer. Hopefully this will eliminate my habit of allowing finished books to pile up in a to-be-blogged pile, which results in multiple entries posted all at once with long periods between them. And now, on to the real business of this entry:

This is the first blog entry I'm writing on my iPad, using an app called Blogger+. My new plan is to write and upload text whenever/wherever I finish a book (hotel, bed, a coffee shop) and then add the finishing touches (pictures, links, and proofreading) when I am at a desktop computer. Hopefully this will eliminate my habit of allowing finished books to pile up in a to-be-blogged pile, which results in multiple entries posted all at once with long periods between them. And now, on to the real business of this entry:Like many of the comics I follow, The Unwritten was recommended by my sister Sarah. Since Sarah is a librarian and knows me better than anyone else, her recommendations are a custom fit, so it's no surprise that I enjoy this comic. All comics take some time to develop, though, and it's in this third story arc that I am beginning to feel a real appreciation for The Unwritten.

The authors of this series are committed to the idea that stories have power--quite literally and magically. The comic's unwilling hero Tommy/Tom Taylor struggles with the legacy his author father left him--first as model for his father's popular boy-wizard book character and now, as an adult, as role model to people around the world (imagine Harry Potter on an even bigger scale), who have a hard time separating real-world Tom from fictional Tommy. Even more importantly, though, Tom faces a struggle against a mysterious Cabal that seeks to undo or influence stories in order to control events in the world. While the premise of words having power is interesting in itself, it's the weaving of literature--classic and popular--throughout that make this series particularly compelling. In a single issue within this trade, there are references to Dickens, The Lord of the Rings, Shakespeare's Henry the Fourth, Fielding, Malory, and the tale of Merlin--heavily dosed with J.K. Rowling, with a mention of the Big Brother and Britain's got talent reality shows thrown in for good measure. In a further creative twist, one issue is printed as a pick-a-story book, in which the reader chooses between options at regular intervals to move between 60 half-page story fragments. Overall, this comic is a true reading pleasure for book and word enthusiasts.

Friday, December 16, 2011

98.11: American Vampire, Volume 2, by Scott Snyder (writer), Rafael Albuquerque and Mateus Santolouco (artists) (trade hardcover, issues 6-11, 2010-11)

When reviewing Volume 1 of American Vampire (link to full entry 46 here), I commented on Stephen King's contribution to the series: "Snyder's

chapters are better written. . . . King is a gifted storyteller, and I'm sure

that more practice will lead him to excellence in the comic format as

well. In fact, the second trade was just released, so I'll soon be able

to report on his progress." I'm sorry to tell you this, but you won't be getting that report. Having given his name and clout to the series, it appears King dropped out of the project after concluding the first story arc. While it's disappointing not to have the opportunity to see King develop as a comic writer, in reality it's not a loss to the series. If anything, the narrative consistency provided by Snyder as sole storyteller--and the high-quality illustration provided by Albuquerque--make volume two of the series that much better than its debut collection.

Having established the premise for a new breed of daytime vampire in volume one, volume two moves forward a bit in time. Still in the American west, the main storyline it set in Las Vegas in the mid 1930s, when the town is beginning its boom in gambling and prostitution in order to meet the interests of the 3,000+ workers involved in the construction of the Hoover Dam. Skinner Sweet is still evil vampire number one, but his progeny, Pearl, lets her claws out after years of domestic bliss, and Pearl's own offspring, Hattie Hargrove, is released from the prison she's been held in for years. With three American vampires on the loose, volume three promises to be killer.

Having established the premise for a new breed of daytime vampire in volume one, volume two moves forward a bit in time. Still in the American west, the main storyline it set in Las Vegas in the mid 1930s, when the town is beginning its boom in gambling and prostitution in order to meet the interests of the 3,000+ workers involved in the construction of the Hoover Dam. Skinner Sweet is still evil vampire number one, but his progeny, Pearl, lets her claws out after years of domestic bliss, and Pearl's own offspring, Hattie Hargrove, is released from the prison she's been held in for years. With three American vampires on the loose, volume three promises to be killer.

97.11: Safe as Houses, House of Mystery 6, by Matthew Sturges, Luca Rossi, Werther Dell-Edera, and Jose Marzan, Jr. (tade paperback, issues 26-30, 2010)

I almost gave up on HoM after trade five, I must admit. It just got a bit too crazy for me, and that's saying a lot for a series that requires you to accept a LOT of craziness. It wasn't the appearance of sort-of-dead relatives, suicidal (or killed) poets, the fictional becoming real, or a house that is no longer a house that got to me, however: it was the chaos. I felt that I was losing my grip on the story line in the last arc; too many things were happening too quickly for me to follow. I just looked back at my review of trade five (Here's the link if your interested.) and am amused to note that I didn't comment on my befuddlement. Instead, I essentially summarized the basic premise of the series and left it at that. In retrospect, I recognize this as a classic strategy my students used when faced with a challenging task: deflect or backtrack to discuss something with which you are comfortable.

Fortunately, trade six slows down a bit and mainly follows a single story arc, with only a couple of tangents. Sure, that single plot might involve Fig (the main character, whose vivid imagination is responsible for the existence of the mystery house and multiple worlds) and the goblins being called upon by witches in order to defeat the Thinking Man, flying robots, huge carnivorous earthworms (think Dune), and an immense monster dampening the torch needed to keep the Summerlands alive. And, yes, the victory comes when Turgis, a gay goblin, takes over leadership to lead the goblin army (explaining to the former leader as he kills him, "It takes great strength to be gay in this world.") and Fig invents a "big, swirly, cutty thing" (looking like an immense length of toilet paper with a smiley face on it, no less) to kill the monster. Still, this is imagination and mystery I can wrap my head around and follow, and even the few tangents clarified some loose strands from trade five. I'm glad to have things sorted out now, as the concepts of imagination, creation, and reality that originally attracted me to the series are so compelling.

One thing this experience underscores for me is a major difference between classic and modern comics. While characters in early comics did evolve and plots built, you could pretty much pick up any single issue and have a coherent story to read. This is not the case of most current adult series, which depend on readers having enough back story to muddle through some fuzzy parts, often reaching very-limited conclusions within story arcs. If I had picked up trade five without having read the earlier HoM issues, I would have put it aside within a few pages--convinced it was complete rubbish. And, I would have missed out on some thought-provoking ideas as a result. The bottom line: if a comic series appeals to you for some reason, start from issue one.

Fortunately, trade six slows down a bit and mainly follows a single story arc, with only a couple of tangents. Sure, that single plot might involve Fig (the main character, whose vivid imagination is responsible for the existence of the mystery house and multiple worlds) and the goblins being called upon by witches in order to defeat the Thinking Man, flying robots, huge carnivorous earthworms (think Dune), and an immense monster dampening the torch needed to keep the Summerlands alive. And, yes, the victory comes when Turgis, a gay goblin, takes over leadership to lead the goblin army (explaining to the former leader as he kills him, "It takes great strength to be gay in this world.") and Fig invents a "big, swirly, cutty thing" (looking like an immense length of toilet paper with a smiley face on it, no less) to kill the monster. Still, this is imagination and mystery I can wrap my head around and follow, and even the few tangents clarified some loose strands from trade five. I'm glad to have things sorted out now, as the concepts of imagination, creation, and reality that originally attracted me to the series are so compelling.

One thing this experience underscores for me is a major difference between classic and modern comics. While characters in early comics did evolve and plots built, you could pretty much pick up any single issue and have a coherent story to read. This is not the case of most current adult series, which depend on readers having enough back story to muddle through some fuzzy parts, often reaching very-limited conclusions within story arcs. If I had picked up trade five without having read the earlier HoM issues, I would have put it aside within a few pages--convinced it was complete rubbish. And, I would have missed out on some thought-provoking ideas as a result. The bottom line: if a comic series appeals to you for some reason, start from issue one.

96.11: No Way Out, The Walking Dead Volume 14, by Robert Kirkman (writer), Charlie Adlard (inker), and Cliff Rathburn (gray tones), (trade paperback, issues 79-84, 2011)

It recently become popular as a television show, but The Walking Dead began as a comic series in 2006. (Since I started this blog in 2011, only one other review can be found here, for trade 14.) I started following it shortly after encountering the authors at an Image signing table at Comic Con 2006. What started out from circumstance and curiosity--I was relatively new to comics and testing the waters as to what was out there--has grown into a full appreciation for a well-written and illustrated series.

In this story arc, the uneasy comfort and quiet the original cast of survivors have enjoyed in a walled city is shattered when gunshots draw an entire herd (hundreds) of the dead to their walls. The ensuing gore-fest is action packed. As human and zombie bodies pile up around them, the characters further their lessons of loyalty, risk, survival, and zombie ass-kicking (or skull smashing, as is actually the case). More importantly, despite the carnage and stress, the book ends with a feeling not evident in recent volumes: hope. Ultimately, I think it's that element that keeps readers reading. And the zombies, of course.

In this story arc, the uneasy comfort and quiet the original cast of survivors have enjoyed in a walled city is shattered when gunshots draw an entire herd (hundreds) of the dead to their walls. The ensuing gore-fest is action packed. As human and zombie bodies pile up around them, the characters further their lessons of loyalty, risk, survival, and zombie ass-kicking (or skull smashing, as is actually the case). More importantly, despite the carnage and stress, the book ends with a feeling not evident in recent volumes: hope. Ultimately, I think it's that element that keeps readers reading. And the zombies, of course.

Thursday, December 15, 2011

95.11: Losers in Space, buy John Barnes (advance uncorrected proof, publication April 2012)

Part of the fun at the NCTE Annual Convention is trolling the exhibit area for freebies. I'm pretty cautious about what I pick up, since I have to haul it across country, and I try to stick to carry-on luggage in my travels. However, the promising sales pitch for this book--teens seeking fame by stowing away on a spaceship with a sociopath loose among them--was strong enough for the novel to make it into my bag. And, pretty much, the sales pitch tells you what you need to know about the book; I'd likely add "futuristic Breakfast Club" to the description to complete the plot. (Of course, today's teen may not find this addition illuminating, but GenXers will get it.) One thing that makes this novel stand out a bit are the 16 regular excerpts--entitled "Notes for the Interested"--that provide explanations of culture, science, and math concepts relevant to the plot. As the book itself points out, these tangents aren't essential to the storyline and an uninterested reader could skip them. Hopefully, though, while considering the effects of celebrity, social media, and romance, a few teen readers may also pick up a few educational tidbits.

94.11: Finger Lickin' Fifteen, by Janet Evanovich (iBook, original publication date 2009)

I've posted entries about a number of books from Evanovich's Stephanie Plum series, so if you are in need of the back story, take a few minutes to visit these earlier entries: Troublemaker (entry 25) and Eleven on Top, Twelve Sharp, Lean Mean Thirteen, and Fearless Fourteen (entries 38-41). As I do when reading every book about the hapless Jersey bail bonds agent, while reading Fifteen I alternately found myself wondering why I was reading such silly stuff and laughing hysterically. I've said it before: for simple fun reading, you can't beat this series.

In Fifteen the caper includes a barbecue contest, a maniac with a cleaver, and a serial arsonist. But really, who cares? The pleasure here is in the regular cast of characters, silly incidents, and zingy one-liners. I smile just thinking about it and plan to upload Sizzling Sixteen soon.

In Fifteen the caper includes a barbecue contest, a maniac with a cleaver, and a serial arsonist. But really, who cares? The pleasure here is in the regular cast of characters, silly incidents, and zingy one-liners. I smile just thinking about it and plan to upload Sizzling Sixteen soon.

93.11: The Mystery of Grace, by Charles de Lint (2009 Hardcover)

De Lint is a "master of contemporary magical fiction," claims his book-cover biography, and the evidence firmly supports this. I discovered and quickly devoured the master's Newford series approximately five years ago and have kept up on new releases since then (visit this link to see the 24 titles, the most recent of which was released in 2009). The use of "series" is a bit misleading here, as the books don't come out as volumes of an ongoing saga. Instead, it's the setting--the fictional North American city of Newford (a hodgepodge of many large cities)--and semi-regular cast of characters--both real and supernatural--that unite the books. There may be several books in which a previously primary character does not appear at all, followed by one in which he/she/it appears tangentially, and and then four or five books down the line finally ends up a focus again. Likewise, events and areas in Newford occasionally overlap, but just as often whole new areas of the city are explored. The final result is a richly imagined realistic world in which the improbable often occurs.

In The Mystery of Grace, the improbable is still central to the story, but the setting and characters are new. It's essentially a love story set in the American Southwest, but otherworldly elements--such as death--complicate the tale. Like all of de Lint's novels, there are many meaning-of-life questions considered without any answers reached. And, while I enjoyed the book for its non-conclusive exploration, it left me a bit dissatisfied. Partly I missed the richness of the Newford world, but I was also a bit annoyed by the overt "spirituality" of the book. I'm not sure if it's de Lint or me who has changed, but the religious connotations struck me as more dominant in this book than his earlier works. While I would highly recommend it to the increasing number of people who consider themselves "spiritual, non-religious," those with more traditional religious beliefs or those without religious belief may be less enthralled. Instead, I'd recommend checking out the Newford series.

In The Mystery of Grace, the improbable is still central to the story, but the setting and characters are new. It's essentially a love story set in the American Southwest, but otherworldly elements--such as death--complicate the tale. Like all of de Lint's novels, there are many meaning-of-life questions considered without any answers reached. And, while I enjoyed the book for its non-conclusive exploration, it left me a bit dissatisfied. Partly I missed the richness of the Newford world, but I was also a bit annoyed by the overt "spirituality" of the book. I'm not sure if it's de Lint or me who has changed, but the religious connotations struck me as more dominant in this book than his earlier works. While I would highly recommend it to the increasing number of people who consider themselves "spiritual, non-religious," those with more traditional religious beliefs or those without religious belief may be less enthralled. Instead, I'd recommend checking out the Newford series.

92.11: Full Dark, No Stars, by Stephen King (2010 hardcover)

I'm not a fan of short-story collections, preferring full-length novels because of their richer character and plot development. There are a few authors, however, for whom I make an exception and check out their shorter fiction, and King is among those. I know there are many people who might not accept King's work as serious "literature" because of his frequent forays into the supernatural, fantasy, and flat-out weird, but I strongly feel that's a narrow view--and one all too commonly held when it comes to authors of SciFi and fantasy. In truth, I feel there are few writers today who have the narrative skill and storytelling power King exhibits again and again, across genre and format.

The four stories in this collection (called "long stories" on the book jacket) aptly demonstrate King's remarkable ability to engage readers and draw them through to the plot's conclusion--despite the fact that the tales told are dark and distasteful. As soon as the premise of each story became clear (murder of a spouse, betrayal of a best friend, rape and revenge, discovery of a spouse's horrible secret), I paused to think about whether I really wanted to continue. However, as any fan of King knows, that opportunity to consider turning back came a little too far down the road: having started the trip under King's skillful direction, I felt compelled to see the journey though. Even knowing there were likely no "happy" endings, and further burdened by the fact that there were no supernatural elements (which would at least allow me the luxury to discount them as improbable), I continued to the destination King set. And, as disturbing as those conclusions were, amongst my feelings of relief upon completing the book, I also experienced a moment of joy: the joy of having a light shone into the darkness to reveal what resides there--without needing to investigate it alone.

The four stories in this collection (called "long stories" on the book jacket) aptly demonstrate King's remarkable ability to engage readers and draw them through to the plot's conclusion--despite the fact that the tales told are dark and distasteful. As soon as the premise of each story became clear (murder of a spouse, betrayal of a best friend, rape and revenge, discovery of a spouse's horrible secret), I paused to think about whether I really wanted to continue. However, as any fan of King knows, that opportunity to consider turning back came a little too far down the road: having started the trip under King's skillful direction, I felt compelled to see the journey though. Even knowing there were likely no "happy" endings, and further burdened by the fact that there were no supernatural elements (which would at least allow me the luxury to discount them as improbable), I continued to the destination King set. And, as disturbing as those conclusions were, amongst my feelings of relief upon completing the book, I also experienced a moment of joy: the joy of having a light shone into the darkness to reveal what resides there--without needing to investigate it alone.

91.11: The Physick Book of Deliverance Dane, by Katherine Rowe (2009 hardcover)

I remember being fascinated by the Salem witch trials when I was a teen, but since then I haven't given them much thought. This novel does a nice job of establishing a believable context for a story about a young scholar who discovers a "lost" Salem witch, never recorded in history books. The witch also ends up being her great-great grandmother, and the story's protagonist follows the chain of succession to the modern day, only to find that she herself is a witch--with inherent witchy powers. (The author bio informs the reader that Howe herself is the descendant of two women involved in the Salem trials--one of whom was executed--although it doesn't, alas, state whether she has special powers.) In addition to a good tale, the novel explores the role of "wise" women in pre-American European settlements, provides background on the witch trials in the 1600s, and encourages the reader to consider the ways in which societies can make something "real" for periods of time.

Thursday, December 1, 2011

90: Witch & Wizard, by James Patterson with Gabrielle Charbonnet (2009 paperback)

The first book in one of Patterson's co-authored (one reason for his prolific production) TeenLit series, Witch & Wizard tells the story of a brother and sister dragged from their homes and imprisoned in the middle of the night by a newly "elected" totalitarian regime, which promptly charges and convicts them of witchcraft. While formerly unaware of their powers, the teens come into their own through a process of conflict and need for survival and join a group of runaway children set on (of course) saving the world. I wouldn't say it's the best of its type, and I prefer Patterson's Maximum Ride series (entries 87-89), but the straight-forward style and sense of humor will appeal to Tween and Teen boys and girls.

87-89: The Angel Experiment, School's Out Forever, and Saving the World (Maximum Ride books 1-3), by James Patterson (iBooks, originally published 2007/8)

One of the things I most enjoy about national conferences is the authors and keynote speakers that populate them. During the National Council of Teachers of English Convention in Chicago this November, my colleague Marsha and I treated ourselves to two lunches--the first with the wonderful poet Billy Collins and the second a combined gig featuring James Patterson and Anthony Horowitz--two TeenLit authors. While I had read a couple of Patterson's adult thrillers in airports over the years, I hadn't checked out his teen offerings. Since Marsha started with the Maximum Ride series (he has many), I decided to start there.

The books require readers to accept the premise that there has been successful hybridization across species--genetic manipulation that has resulted in Max and her "flock." By initial appearances human, avian genes have been added that resulted in the kids--six of them ranging from 17-year-old max to 8-year-old Angel--growing winds, light bones, super strength, and any number of amazing abilities that unfurl daily (mind control, super speed, talking to fish, etc.).

The science may be iffy, but the mad scientists, who kept the children in cages for years to experiment on them and are, of course, planning to take over the world, add just the details needed to accept the idea. These three books follow Max and her flock as they learn to live on their own, look for their birth parents, and--yes--save the world.

All joking aside, the plots are fast-paced and adventurous and the kids are appealing, and Patterson's bare-bones writing style suits the teen genre well. The fact that he was a brilliant conversationalist at the conference adds to my review, no doubt, but these are worth checking out and sharing with young adult readers--both boys and girls.

The books require readers to accept the premise that there has been successful hybridization across species--genetic manipulation that has resulted in Max and her "flock." By initial appearances human, avian genes have been added that resulted in the kids--six of them ranging from 17-year-old max to 8-year-old Angel--growing winds, light bones, super strength, and any number of amazing abilities that unfurl daily (mind control, super speed, talking to fish, etc.).

The science may be iffy, but the mad scientists, who kept the children in cages for years to experiment on them and are, of course, planning to take over the world, add just the details needed to accept the idea. These three books follow Max and her flock as they learn to live on their own, look for their birth parents, and--yes--save the world.

All joking aside, the plots are fast-paced and adventurous and the kids are appealing, and Patterson's bare-bones writing style suits the teen genre well. The fact that he was a brilliant conversationalist at the conference adds to my review, no doubt, but these are worth checking out and sharing with young adult readers--both boys and girls.

86: Julian Comstock: A Story of 22nd-Century America, by Robert Charles Wilson (2009 hardcover)

I chose this book based on Amazon's recommendation and the fact that both Cory Doctorow and Stephen King provided blurbs for the jacket. King said, "Robert Charles Wilson is a hell of a storyteller," and since I think King is quite the storyteller himself, I thought this was pretty high praise. The book turned out compelling enough to keep me going through 400+ pages of small font (My perspective has been skewed by all the TeenLit I read these days.), but it's a hard book to describe in many ways.

Mainly the problem of describing the novel arises in assigning it a genre. Wilson is considered a SciFi author, and I suppose that loosely fits things--but very loosely. The story is set in a futuristic 22nd-Century America, but one that looks much more like things did in the 18th century. There are scattered pockets of technology, but on the whole it's much more of a feudal society, with landowners and serfs, a mixed civil and religious political structure with military leanings. There's a constant war that is being waged to maintain the American borders--and a corresponding flag of 13 stripes and 60 stars. It's low tech enough to keep it out of the Steampunk genre, yet there's a flavor of something futuristic at the same time--in a collapse type of way common to Post-Apocalyptic novels, but well after any horror has dissipated.

With all that aside, the novel is primarily a story of friendship--between a lower-born aspiring author (the book's narrator) and the aristocratic son of the slain US President. The two travel across country, engage in numerous battle scenes, make critiques of high society and religion, and comment on socialism and totalitarianism. All in all there is a bit of something in here for everyone, and while I think that it's a more male-oriented plot, there is enough drama and interest to pull most readers along.

Mainly the problem of describing the novel arises in assigning it a genre. Wilson is considered a SciFi author, and I suppose that loosely fits things--but very loosely. The story is set in a futuristic 22nd-Century America, but one that looks much more like things did in the 18th century. There are scattered pockets of technology, but on the whole it's much more of a feudal society, with landowners and serfs, a mixed civil and religious political structure with military leanings. There's a constant war that is being waged to maintain the American borders--and a corresponding flag of 13 stripes and 60 stars. It's low tech enough to keep it out of the Steampunk genre, yet there's a flavor of something futuristic at the same time--in a collapse type of way common to Post-Apocalyptic novels, but well after any horror has dissipated.

With all that aside, the novel is primarily a story of friendship--between a lower-born aspiring author (the book's narrator) and the aristocratic son of the slain US President. The two travel across country, engage in numerous battle scenes, make critiques of high society and religion, and comment on socialism and totalitarianism. All in all there is a bit of something in here for everyone, and while I think that it's a more male-oriented plot, there is enough drama and interest to pull most readers along.

Tuesday, October 25, 2011

85: Wonderstruck, by Brian Selznick (2011 hardcover)

Those who read Selznicks's The Invention of Hugo Cabret--an illustrated novel describing a young boy's secret life living in a train station--have been eagerly awaiting the release of Wonderstruck. After reading it, I can't see any of these folks being disappointed, and I suspect those who start with this book will go back and read the earlier release. Like tIoHC, Wonderstruck integrates full pages of text with full pages of drawing--hence the illustrated-novel versus graphic-novel designation. In this book, however, there is even more illustration, adding to the richness of the reading experience. Even more interestingly, though, the book starts by alternating text pages of one story with illustrated pages of another story. The two seem completely separate and unconnected at first, but over the course of the novel the two story lines merge interestingly.

The book is enchanting and unusual, and I thoroughly enjoyed it. However, after finishing, I began reflecting on the underlying premise of both books. In Hugo, a 12-year-old orphaned boy lives in a Paris train station after the death of his father (mother already deceased); in Wonderstruck, a similarly-aged boy runs aways from home after the death of his mother (father already absent/unknown), traveling from rural Minnesota to hide out in NYC's Museum of Natural History. Both successfully manage to feed themselves, remain safe, and meet other people. I can't help but wonder about this, as it's hard to imagine such success stories. I know this is fiction and allows room for fantasy--and many Tween/Teen books rely on a premise of absent parents and independence--but it's a bit scary too. Of course, I'm not in any way suggesting this book should be kept from young kids, and I don't believe it would cause them to run away, but I certainly think there are some conversations that could be held around the premise. After all, there's a difference between this type of "fantasy" world and one that you find through a secret door in the back of a wardrobe: it is accessible. And, there are no talking animals to offer guidance.

[Also visit my friend/colleague Stephanie Vanderslice's blog Wordamour for some more conversation on this concept of real world fantasy.]

The book is enchanting and unusual, and I thoroughly enjoyed it. However, after finishing, I began reflecting on the underlying premise of both books. In Hugo, a 12-year-old orphaned boy lives in a Paris train station after the death of his father (mother already deceased); in Wonderstruck, a similarly-aged boy runs aways from home after the death of his mother (father already absent/unknown), traveling from rural Minnesota to hide out in NYC's Museum of Natural History. Both successfully manage to feed themselves, remain safe, and meet other people. I can't help but wonder about this, as it's hard to imagine such success stories. I know this is fiction and allows room for fantasy--and many Tween/Teen books rely on a premise of absent parents and independence--but it's a bit scary too. Of course, I'm not in any way suggesting this book should be kept from young kids, and I don't believe it would cause them to run away, but I certainly think there are some conversations that could be held around the premise. After all, there's a difference between this type of "fantasy" world and one that you find through a secret door in the back of a wardrobe: it is accessible. And, there are no talking animals to offer guidance.

[Also visit my friend/colleague Stephanie Vanderslice's blog Wordamour for some more conversation on this concept of real world fantasy.]

84: Revolution, by Jennifer Donnelly (2010 hardcover)

This is the second Donnelly book I read, and it was as good or better than the first. A troubled American teenager travels to Paris with her father and discovers a journal that takes her back centuries in time--in both a figurative and, eventually, literal sense. It's a great coming-of-age story combining history and fantasy in an engaging manner. There's lots to be learned here, and teen girls will love the romance and angst as well.

83: Revolver, by Matt Kindt (2010 paperback)

In college, my roommate loved it when our digital clock read 11:11--whether morning or night. It's only one of many small details of this graphic novel that make me enjoy it, but it's a good example of the mundane things that end up being more significant as Revolver continues. In this instance, 11:11 is the time when Sam crosses back and forth from his typical life--a boring job, a girlfriend he adores, and furniture shopping--to another, parallel life--featuring a post apocalyptic version of the same people and places. Or does he? With an intelligent story line, weird coincidences, and modern psychobabble, it's hard to know which of Sam's lives is real. Or if either is.

82: Morning Glories Volume 2, by Nick Spencer (words), Joe Eisma (art), and Rodin Esquejo (covers). (2011 paperback trade, borrowed from Sarah)

In volume one, three teen boys and three teen girls enter Morning Glory Academy, a prestigious prep school with a sinister subplot and faculty. Alternately fighting for their lives and with each other, the characters are further developed in volume 2, which consists of an "origins" story for each of the six main players. While the stories do little to make the teens more appealing, they do deepen the evil nature of the school and lead the reader to fear the possible mission these kids could be sent on. It's dark horror dressed up in short skirts and prep ties--a delight for anyone who understands the malignancy of the teen years.

81: Lost & Found, by Shaun Tan (2011 hardcover)

I picked up Tan's wordless 2007 picture book entitled The Arrival at a California Association of Teachers of English conference a few years ago. Beautifully illustrated with collage and multimedia art, Tan does a remarkable job showing the experience of immigration in a manner appealing to its targeted 7th-grade-and-up audience. When I cam across this collection of 3 shorter pieces, I impulsively bought it and read the entire thing while waiting for a meeting. Like Tan's earlier works, Lost & Found is a beautiful book: each page contains collage-style artwork with an infinite number of details. Like earlier work, this too is identified as being for ages nine and up. I was actually a bit surprised by the low age listing, to be quite honest: the stories share tales of depression, otherness, and conquest/colonization. Then I realized that the art aspect of the book--words included this time--allows for multiple levels of knowing and feeling. In all, it's big, beautiful, and very thought-provoking for all ages.

80: Zero History, by William Gibson (2010 hardcover)

After I read Neuromancer (published in 1984) in the early 90s, I quickly devoured everything Gibson had written, and I have since kept up with his releases. I was attracted to the tech themes of his early cyber-punk books and I continue to admire the way he investigates the concept of "reality" and how it is created or influenced. In this novel he returns to some of the characters of Spook Country, which was described by the media as a "post-9/11 thriller." As best I can tell, thrillers of this genre focus on edgy characters that are either bored or fighting for their lives, depending on the moment. Quite frequently, the thing they are fighting for don't seem particularly important (fashion, in this instance) and the bad guys and good guys are hard to discern. At times I found myself wondering why I was reading the book at all, but I was compelled to continue. There's always the feeling that the answer--not only to the current story, but to life itself--will appear on the next page of a Gibson novel. I keep turning them.

79: Troubletwisters, Book 1, by Garth Nix and Sean Williams (2011 hardcover)

I keep coming across fantasy books by Nix, so I decided to try this Tween book to see what I thought of his work. As things go in books for this age group, Troubletwisters (yes, all one word, which bugged me immensely) was a relatively gripping read, fraught with the usual missing parents (work), visit to strange relative (grandmother), and oncoming powers (control of weather conditions). The main characters are Jaide and Jack--twins who don't necessarily conform to gender roles (Jaide is faster, Jack more thoughtful)--and there are enough evil characters, talking animals, and bugs to make kids this age happy. I'll take a look at another Nix book to see what I think, and I'll keep my eyes open for Troubletwisters Book 2, as promised by the this volume's title.

78: Shades of Gray: The Road to High Saffron, by Jasper Fforde (2009 hardcover)

I enjoyed the Thursday Next series Fforde started a number of years back, although I lapsed and haven't read the most recent volumes. When I came across this in the Borders 50% off sale, though, I decided to give it a try. In this novel, Fforde's zany humor is evident, as is his love of words and vivid language. Here, however, we also have the added excitement of a whole new dystopic world called Chromatacia--one based on color and the ability of humans to perceive the colors around them--an ability which defines their class status within the Colortocracy, the jobs they can hold, and even who they can love or marry. This is Fforde at his best, and I'm inspired to catch up on the Thursday Next series as well!

75-77: Air 1 Letters from Lost Countries, 2 Flying Machine, and 3 Purelandby G. Willow Wilson (writer) and M.K. Perker (artist). (paperback, issues 1-5 2009, issues 6-10 2009, issues 7-11 2009-10)

A comic written about a flight attendant with a fear of heights is a winning premise to begin with, but throw in an exotic boyfriend, a country that doesn't exist but can still be visited, and historic figures like Amelia Earheart, and this comic makes a pretty winning combination. The plot occasionally drags and the main character can be a bit of a sap, but overall I'll add this to the comic series I follow.

A comic written about a flight attendant with a fear of heights is a winning premise to begin with, but throw in an exotic boyfriend, a country that doesn't exist but can still be visited, and historic figures like Amelia Earheart, and this comic makes a pretty winning combination. The plot occasionally drags and the main character can be a bit of a sap, but overall I'll add this to the comic series I follow.Thursday, September 22, 2011

69: A Great and Terrible Beauty (Gemma Doyle, Book 1), by Libba Bray (2003 paperback)

Sent to an English boarding school after witnessing the death of her mother under mysterious cicumstances in colonial India, Gemma Doyle gets caught up in the occult. The first in a series, the plot is somewhat interesting, but the overall premise wasn't enough to make me pick up the next volume. Those who enjoy magic and the paranormal may fare better. And, check out Bray's more contemporary novels, Going Bovine and Beauty Queens for some quality satire written for a teen audience.

68: Flip, by Martyn Bedford (2011 hardcover)

A teen boy wakes up in the body of another, more popular and wealthy teen boy. He struggles to find what has happened to his own body while also struggling to maintain appearances and play a new role. This is an interesting and well-paced read which will be enjoyed by girls and boys alike.

67: Eli the Good, by Silas House (2009 paperback)

I've seen this book listed as a top pick in a number of places, but I kept putting it down each time I came across it. I'm less compelled to read TweenLit than TeenLit, and Vietnam-era references aren't my favorite either. It's hard to ignore such regular recommendations, though, and I finally broke down and bought Eli on a visit to my local bookseller. And, the critics were right: this is a charming and compelling novel--a wonderful look into the summer of 1976 and the life of a young boy grappling with the effects Vietnam had on his country, his veteran father, and his family.

I turned nine the August after America's Bicentennial celebration, which gives me a natural affinity for the book's 10-year-old author. While Eli's family and community are different than the one in which I was raised, the period details in the book--fashion, music, social norms--are genuine and richly developed. It's a rare book that can make you feel as if the sun is beating on your back, the strains of Cat Stevens and Van Morrison are ringing in your ears, and the scent of evaporating summer rain is invading your nostrils. House does all this and more, though. I'm reminded of another of my favorite books in recent years, The Mammoth Cheese by Sheri Holman, which also focuses on Americana, celebration, and turmoil.

In a nutshell, Eli the Good is an immersion. Take a dip in this wonderful book, swim through its pages, and emerge both tired and exhilarated.

I turned nine the August after America's Bicentennial celebration, which gives me a natural affinity for the book's 10-year-old author. While Eli's family and community are different than the one in which I was raised, the period details in the book--fashion, music, social norms--are genuine and richly developed. It's a rare book that can make you feel as if the sun is beating on your back, the strains of Cat Stevens and Van Morrison are ringing in your ears, and the scent of evaporating summer rain is invading your nostrils. House does all this and more, though. I'm reminded of another of my favorite books in recent years, The Mammoth Cheese by Sheri Holman, which also focuses on Americana, celebration, and turmoil.

In a nutshell, Eli the Good is an immersion. Take a dip in this wonderful book, swim through its pages, and emerge both tired and exhilarated.

Tuesday, August 30, 2011

65: Blackout, by Connie Willis (2010 paperback; hardcover published 2010)

Over the summer, NPR put out "Your Picks: Top 100 Science-Fiction, Fantasy Reads." It's a decent list, although lacking a bit in female authors (Octavia Butler is noticeably and disappointingly absent, for instance.). One female author on the list with whom I was not familiar is Connie Willis, whose Doomsday Book came in at 97. While scavenging the close-out sale at Border's, I came across Blackout and decided to give it a try.

At first I had quite a hard time with the book, and I couldn't figure out why. It wasn't because of the content or premise, as its storyline of time-traveling historians appealed to me. I was a bit less interested in the WW II focus, but that still didn't explain it. Finally, I realized that the author's extensive use of dialogue--both external and internal--was putting me off. This may have been exacerbated by the fact that the language is British English in the early 1940s, a vernacular similar enough to mine so that I felt it should seem comfortable, but different enough so that it really wasn't. Things felt stilted and formal, which I suppose was true of the time itself as well as the language, when compared to today.

Ultimately I grew to enjoy the book and the opportunity to peek into 1940 London during the Blitz. Because the narrators are historians, traveling back in time to study particular events, it seems natural to have historical information and a narrative storyline jumbled together. And, this is really the way I like my history lessons: fictional and story driven. I'm taking a bit of a break from the war, but I'll be back sometime with a review of the follow-up book, All Clear.

At first I had quite a hard time with the book, and I couldn't figure out why. It wasn't because of the content or premise, as its storyline of time-traveling historians appealed to me. I was a bit less interested in the WW II focus, but that still didn't explain it. Finally, I realized that the author's extensive use of dialogue--both external and internal--was putting me off. This may have been exacerbated by the fact that the language is British English in the early 1940s, a vernacular similar enough to mine so that I felt it should seem comfortable, but different enough so that it really wasn't. Things felt stilted and formal, which I suppose was true of the time itself as well as the language, when compared to today.

Ultimately I grew to enjoy the book and the opportunity to peek into 1940 London during the Blitz. Because the narrators are historians, traveling back in time to study particular events, it seems natural to have historical information and a narrative storyline jumbled together. And, this is really the way I like my history lessons: fictional and story driven. I'm taking a bit of a break from the war, but I'll be back sometime with a review of the follow-up book, All Clear.

Tuesday, August 16, 2011

64: Delirium: The Special Edition, by Lauren Oliver (2011 hardcover)

It's probably not fair to this book that I (temporarily, I'm guessing) reached my fill of teen dystopian romances midway through reading it. It's a genre I generally like, but this one leaned a bit too far toward the romance end of things for my taste; I can tolerate the romance as long as the world developed behind it is interesting and compelling. In this book, however, the romance is center stage.

Why this took me by surprise, I don't know, as it's basically stated on the jacket cover. After all, 17-year-old Lena lives in a world where love is considered a life-threatening disease, where 60+ years earlier scientists came up with a surgical "cure" to relieve people of its symptoms. The surgery to prevent delirium takes place at age 18, though, and any reader of TeenLit knows what will happen in those circumstances--especially after learning that Lena's mother's cure just never took, even after three attempts, and she ended up committing suicide when Lena was a child. And then she meets a boy from the wilds: the areas outside the highly policed and controlled cities, where people don't get the cure and still choose their own mates, ways of life, etc.

Despite my lack of enthusiasm for Delirium, I must admit I'll likely read the sequel; writing about it now makes me consider some of the story elements and concepts I did like, such as making me reflect in how quickly a culture can be changed due to revolution/technology/chaos. I think I just read myself into a genre rut here and need a bit of a break.

(By the way, if you were wondering what is so special about the Special Edition: there's a Q & A section and the first chapter of the sequel. I actually chose it because I liked the cover better.)

Why this took me by surprise, I don't know, as it's basically stated on the jacket cover. After all, 17-year-old Lena lives in a world where love is considered a life-threatening disease, where 60+ years earlier scientists came up with a surgical "cure" to relieve people of its symptoms. The surgery to prevent delirium takes place at age 18, though, and any reader of TeenLit knows what will happen in those circumstances--especially after learning that Lena's mother's cure just never took, even after three attempts, and she ended up committing suicide when Lena was a child. And then she meets a boy from the wilds: the areas outside the highly policed and controlled cities, where people don't get the cure and still choose their own mates, ways of life, etc.

Despite my lack of enthusiasm for Delirium, I must admit I'll likely read the sequel; writing about it now makes me consider some of the story elements and concepts I did like, such as making me reflect in how quickly a culture can be changed due to revolution/technology/chaos. I think I just read myself into a genre rut here and need a bit of a break.

(By the way, if you were wondering what is so special about the Special Edition: there's a Q & A section and the first chapter of the sequel. I actually chose it because I liked the cover better.)

63: Going Bovine, by Libba Bray (2009 paperback)

A novel about a teen stoner and misfit being diagnosed with Mad Cow Disease doesn't sound particularly funny or inspiring, but in the hands of Libba Bray it becomes just that. After racing through Beauty Queens (reviewed earlier), I knew I had to read more of Bray's work. The fact that this book--with a completely different narrator and premise than Beauty Queens--was equally entertaining leaves me convinced of Bray's gifts as a writer and observer of American society.

One of Bray's talents is to take unlikely protagonists, such as sixteen-year-old Cameron, and turn them into mock-heroic figures. Rather than accepting the limitations of his fatal illness, Cameron embarks on a cross-country journey with a punk angel, a teen dwarf, and a yard gnome/Viking god as companions. The mission? To find the man with a cure for Cameron's illness by searching tabloids, billboards, and random matchbook covers for clues, while also avoiding fire demons and surviving a stay in a cult of happiness. It's a rollicking ride with a surprising conclusion, and it left me wanting more Libba Bray.

In fact, I just picked up the first volume of her Gemma Doyle trilogy, featuring a teen girl in Victorian England. The series looks to be of a completely different genre--light horror, historical fiction--from the books I've already read by Bray, so I'm curious to see how her skills play out. This entire enterprise is a big departure for me, too, as I usually like to read an author's books in the order they were written/published, and this series predates either of her two books I've already read. Stay tuned to see how the experiment works out--and let me know if you've read Bray's work and what you thought.

One of Bray's talents is to take unlikely protagonists, such as sixteen-year-old Cameron, and turn them into mock-heroic figures. Rather than accepting the limitations of his fatal illness, Cameron embarks on a cross-country journey with a punk angel, a teen dwarf, and a yard gnome/Viking god as companions. The mission? To find the man with a cure for Cameron's illness by searching tabloids, billboards, and random matchbook covers for clues, while also avoiding fire demons and surviving a stay in a cult of happiness. It's a rollicking ride with a surprising conclusion, and it left me wanting more Libba Bray.

In fact, I just picked up the first volume of her Gemma Doyle trilogy, featuring a teen girl in Victorian England. The series looks to be of a completely different genre--light horror, historical fiction--from the books I've already read by Bray, so I'm curious to see how her skills play out. This entire enterprise is a big departure for me, too, as I usually like to read an author's books in the order they were written/published, and this series predates either of her two books I've already read. Stay tuned to see how the experiment works out--and let me know if you've read Bray's work and what you thought.

Tuesday, August 9, 2011

62: Matched, by Ally Condie (2010 hardcover)

One of the blurbs on the back jacket of the book calls Matched a "dystopian love story," and I suppose that is as good a descriptor as any. The dystopian part of the description makes it rise above the level of typical teen romance, though, exploring what happens when a society attempts to control every aspect of the lives of its members--from birth (who can bear children, when, and how many), through marriage (if and to whom), and death (by midnight on your 80th birthday). In doing so, Condie encourages her readers to weigh the importance of freedom versus chaos and raises the question of when it's necessary to question authority.

The story kicks off with 17-year-old Cassia riding the train to the city with her parents, her childhood friend and his parents, and many other well-dressed 17-year-olds and their families. As the story unfolds, we learn that the same thing is happening throughout the country, where young men and women are heading to their city hall for a banquet during which they will be introduced to their "match"--the person they will court and then marry at age 21. Characteristics and aptitudes have been entered into a database so that the match chosen for them will be the best possible, ensuring the genetic health of their offspring and a compatible lifestyle for the couple. Cassia has never before questioned the arrangement and looks forward to the unveiling of her match over large TV screens, a system to make matches possible across large geographic areas.

As they must to make a story, things eventually go wrong with Cassia's match, and she begins to question the very basis of her world. In the process, a fascinating social experiment is revealed, wherein people's education, meal preparation, occupation, and leisure time is standardized and scheduled. And, when things aren't going just as you'd hoped, you can always take the blue, green, or red pill that you are required to carry with you at all times.

In many ways, the storyline borrows elements of 1984 and Brave New World: there is a war in the borderlands and technology is highly advanced. Unlike those novels, though, Condie has clearly set Matched up for a sequel--or even more likely in the teen world, as the first installment in a trilogy--and I am looking forward to seeing where it leads.

The story kicks off with 17-year-old Cassia riding the train to the city with her parents, her childhood friend and his parents, and many other well-dressed 17-year-olds and their families. As the story unfolds, we learn that the same thing is happening throughout the country, where young men and women are heading to their city hall for a banquet during which they will be introduced to their "match"--the person they will court and then marry at age 21. Characteristics and aptitudes have been entered into a database so that the match chosen for them will be the best possible, ensuring the genetic health of their offspring and a compatible lifestyle for the couple. Cassia has never before questioned the arrangement and looks forward to the unveiling of her match over large TV screens, a system to make matches possible across large geographic areas.

As they must to make a story, things eventually go wrong with Cassia's match, and she begins to question the very basis of her world. In the process, a fascinating social experiment is revealed, wherein people's education, meal preparation, occupation, and leisure time is standardized and scheduled. And, when things aren't going just as you'd hoped, you can always take the blue, green, or red pill that you are required to carry with you at all times.

In many ways, the storyline borrows elements of 1984 and Brave New World: there is a war in the borderlands and technology is highly advanced. Unlike those novels, though, Condie has clearly set Matched up for a sequel--or even more likely in the teen world, as the first installment in a trilogy--and I am looking forward to seeing where it leads.

Monday, August 8, 2011

60-61: The Maze Runner and The Scorch Trials (Books 1 and 2 of the Maze Runner trilogy), by James Dashner (2009 paperback and 2010 hardcover)

I came across this trilogy in postings on the Centurions of 2011 Facebook page regarding the monthly books members have read. Time and time again, folks commented on these books being among their favorite for the month. With such regular recommendations, a few tantalizing details, and the promise of a maze, how could I resist trying another post-apocalyptic TeenLit series?

I'll have to say that when reading the first third of The Maze Runner, I was less than enthralled. The main character is a whiny, self-centered 16-year-old boy named Thomas, and I felt no kinship with him. Had I been trapped in the center (the Glade) of the maze with him and his 50 or so teen male cohorts, I would have wanted to smack him--and pretty much every one of them--upside the head and told him to get over himself. Sure your memory has been wiped, sure you are trapped in a prison for unknown crimes, and sure horrific creatures lurk in the corridors waiting to kill you, but...sheesh. Enough of the moping and discourteous behavior, Thomas. Snap out of it!

And, of course, he does snap out of it. After all, as in all teen post-apocalyptic tales, these young folks must rise to the occasion. Or be eaten by monsters.

By the middle of the first volume, enthrallment kicked in, and I rushed right on to The Scorch Trials, where the girls finally show up. Rather than the surreal, obviously fabricated maze, the two teen teams now enter the real world--alternating between cities filled with insane, zombie-like Cranks, a nightmare landscape with relentless sun beating down on a desert wasteland, and torrential wind and lightening storms destroying anything alive on said wasteland. It's a world devastated by sun flairs and an extremely contagious fatal disease. And monsters, but different monsters.

I read these first volumes in two days, and despite how busy I am preparing for this Saturday's pig roast and the looming first day of the semester, I'm going to get to Northtown Books as soon as possible to pick up the trilogy's conclusion, The Death Cure.

I'll have to say that when reading the first third of The Maze Runner, I was less than enthralled. The main character is a whiny, self-centered 16-year-old boy named Thomas, and I felt no kinship with him. Had I been trapped in the center (the Glade) of the maze with him and his 50 or so teen male cohorts, I would have wanted to smack him--and pretty much every one of them--upside the head and told him to get over himself. Sure your memory has been wiped, sure you are trapped in a prison for unknown crimes, and sure horrific creatures lurk in the corridors waiting to kill you, but...sheesh. Enough of the moping and discourteous behavior, Thomas. Snap out of it!

And, of course, he does snap out of it. After all, as in all teen post-apocalyptic tales, these young folks must rise to the occasion. Or be eaten by monsters.

By the middle of the first volume, enthrallment kicked in, and I rushed right on to The Scorch Trials, where the girls finally show up. Rather than the surreal, obviously fabricated maze, the two teen teams now enter the real world--alternating between cities filled with insane, zombie-like Cranks, a nightmare landscape with relentless sun beating down on a desert wasteland, and torrential wind and lightening storms destroying anything alive on said wasteland. It's a world devastated by sun flairs and an extremely contagious fatal disease. And monsters, but different monsters.

I read these first volumes in two days, and despite how busy I am preparing for this Saturday's pig roast and the looming first day of the semester, I'm going to get to Northtown Books as soon as possible to pick up the trilogy's conclusion, The Death Cure.

59: Miss Peregrine's Home for Peculiar Children, by Ransom Riggs (2011 hardcover)

When I'm browsing the bookshelves at a store, there are some things that are likely to make me pick up a book and look more closely at the words on its pages: a good cover image, an interesting title, odd sizing, and good color. This book has the first two items on my list, as well as another gimmick within its pages; it includes 40+ vintage pictures throughout, which serve to illustrate an interesting tale. And, as I read more closely, I realized that the photographs aren't mere supplements to the story, but provide additional detail and information to the story itself--a bit like a graphic novel does, although in a more subtle fashion manner. Indeed, the conclusion I reached in reading the book is that the pictures came first. At the very least, some of the photographs were found by the author, inspiring a story that led him to search for more photos to complete the tale.

These aren't simply old pictures, either, but a collection capturing the unusual, the strange, the, well...peculiar. Jacob, the 16-year-old protagonist, is first shown a few of these photographs by his grandfather, a Holocaust survivor and teller of fanciful stories. At least Jacob believes these stories to be fanciful, but upon his grandfather's death he has a glimpse into a world of the peculiar and horrific. Once his eyes have been opened, he can't unsee these strange things, and he actively seeks them out--gaining permission to visit the remote island where his grandfather's orphanage, the name of which provides the title of the novel, was located.

The tale told is charming, action-filled, and old-fashioned in a modern kind of way. It involves characters with unusual talents, time loops, and a boy learning to face himself and the world. It's a good story to begin with, but the photographs raise it to something more.

These aren't simply old pictures, either, but a collection capturing the unusual, the strange, the, well...peculiar. Jacob, the 16-year-old protagonist, is first shown a few of these photographs by his grandfather, a Holocaust survivor and teller of fanciful stories. At least Jacob believes these stories to be fanciful, but upon his grandfather's death he has a glimpse into a world of the peculiar and horrific. Once his eyes have been opened, he can't unsee these strange things, and he actively seeks them out--gaining permission to visit the remote island where his grandfather's orphanage, the name of which provides the title of the novel, was located.

The tale told is charming, action-filled, and old-fashioned in a modern kind of way. It involves characters with unusual talents, time loops, and a boy learning to face himself and the world. It's a good story to begin with, but the photographs raise it to something more.

Wednesday, August 3, 2011

56-58: Shiver, Linger, Forever (Wolves of Mercy Falls trilogy), by Maggie Stiefvater (2009/10 paperback, 2011 hardcover)